Introduction:

As a legendary work in animation film history, Ghost in the Shell (1995) is well known by its philosophical themes and stunning scenes. Received universal acclaim from critics and been widely considered one of the greatest anime films of all time. Ghost in the Shell influenced a number of prominent filmmakers. Including the Wachowskis, creators of The Matrix and its sequels.

Without a doubt, The Matrix (1999) is a Hollywood modern classical science fiction movie, known for the popularized visual effect “bullet time”. It is also an example of the cyberpunk science fiction genre. Reviewers praised The Matrix for its innovative visual effects, shocking plot, and its entertainment.

As many people have already known, The Matrix was inspired by Ghost in the Shell in many ways, “including the Matrix digital rain, which was inspired by the opening credits of Ghost in the Shell, and the way people accessed the Matrix through holes in the back of their necks.”1 However, in this essay, the topic will not focus on how much one looks like the other. Rather the hidden meaning underneath the surface – besides the similar concept or design in two movies, did they serve the same purpose? What makes them different? Is there any new meaning generated? In the following sections, I will focus on two examples, to analysis and illustrate how the similar visual design working under different contexts and serve different functions.

Analysis example 1 – The “wake up” scene

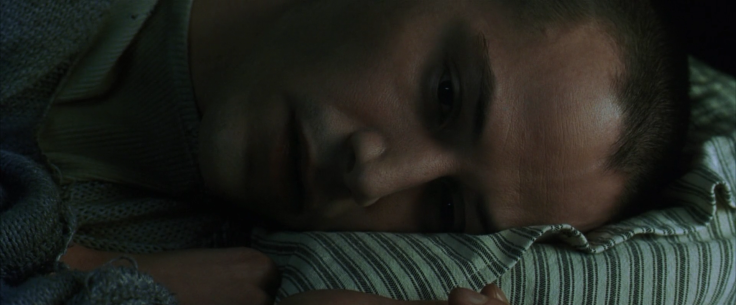

Let’s begin with the “wake up” scene in Ghost in the Shell: the scene took place at beginning part of the film. It starts with a close-up shot of heroine Motoko Kusanagi sleeping on her bed (See Fig. 1.) She opens her eyes, staring at the camera, then looks at her fingers. This is a very humanized behavior. Follow by she wakes up in a completely black room and opens the window. The next shot shows the entire room: there is nothing in her room except the bed (See Fig. 2.) This non-human look (no color, only the bed/window) suggests there is no personality and emotion in her life.

As two main parts of this scene, the shot that Motoko open eyes and the shot shows her room, working together to give the viewer a contrast between humanized behaviors and a non-human life. Such a visual contradiction would give the audience a subconscious impression and prepare them for Motoko’s philosophical dilemmas: Am I a real human? What makes me a real and unique individual? – According to the plot, “The story is set in a dystopian future where technology has reached a point of manipulating human individuals through re-programming one’s memory called the ‘Ghost’, which makes Kusanagi ponder her own reality and identity.”2 Base on the core issue and main theme of the film, the scene here is like an epitomized plot: the whole movie in one moment.

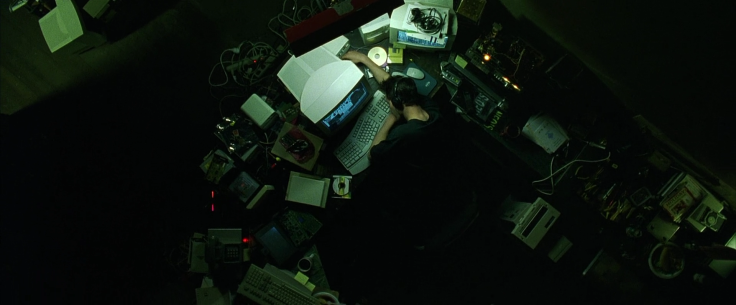

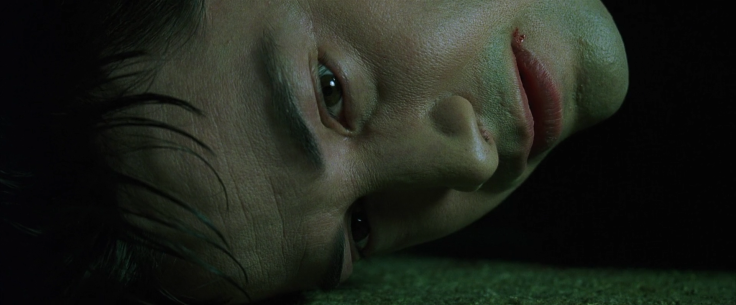

Now let’s take a look at Neo’s “wake up” scene in The Matrix: starts with a close-up shot of computer screen, showing some searching program is running (searching for Morpheus.) Then cut to another close-up of Neo lying on his desk and sleeping (See Fig. 3.) His face has been illumined by the computer screen. This implies he is living in a cyberspace, spends all his life searching and chasing the truth, or someone who knows the truth, like Morpheus. The next two shots showing his room – a place full of computer hardwares, monitors, wires and garbage (See Fig. 4.) Again, it suggests his life is all about seeking an answer. Then, the camera cut to the screen, searching program is gone, only a blank screen showing “Wake up, Neo…” And cut to a close up of Neo’s face, which very similar to the one in Motoko’s wake up scene (See Fig. 5.) His eyes blink and open, staring at the screen. Then he gets up, confused about what happened to his computer.

What interesting is, there are two more “wake up” scenes of Neo in The Matrix. Besides the first one we discussed above, which at the beginning of the movie. The second one is in the middle of the film (See Fig. 6,) after Neo learned the truth from Morpheus, shock and pass out, then wakes up from his coma. The third one is near the end of the movie (See Fig. 7,) after Trinity kisses Neo and telling him he is the one because she loves him and he won’t die, he wakes up from his “death”. Every time Neo wakes up, he will enter another level of his adventure. The three wake up scenes isolates the movie’s three sections: that Neo is living in the Matrix; that he begins to understand the Matrix; and that he becomes “the one” then beyond the Matrix. “Put another way, the film’s three parts are preconscious, conscious and superconscious.”3

By comparing the “wake up” scenes, it clearly shows different usage and purpose. Although they contain similar shots of eyes open, in Ghost in the Shell the wake-up scene helps to give the viewer a paradox feeling of Motoko’s life, and casts a foreshadow to the coming plot. In The Matrix, Wachowskis use the “wake up” scenes to metaphor the different stages of Neo’s evolution and revolution – the journey of his wake up from the Matrix, the path of he becomes “the one.” In other words, Wachowskis using the “wake up” scenes as a storytelling tool, helps to build a complex plot.

Analysis example 2 – The design of “jack-in”

Now let’s talk about another important visual design in both films: the “jack-in” design. If we take a close look, there are similarities and differences at the same time.

On the one hand, we have the design from Ghost in the Shell (See Fig. 8, 9.) It is a multiple jacks interface with a minimalist design, locates on the back of one’s neck. Such a design represents the style of the digital age: combine both function and aesthetic, integrated with the body make it not too obvious. According to the story, characters using these jacks to dive in cyberspace (or hack into someone’s ghost.) Just like using a router or modem to connect our computer to the Internet. It is the basic needs in a cyber age, can be operated by oneself.

On the other hand, we have the design in The Matrix (See Fig. 10, 11.) It is a single jack locates on the back of the head. A pure utilitarianism, function supreme design with the typical cyberpunk style: complicate and clumsy. In the film, a person must has someone’s help to jack-in and hack into the Matrix. The “hole” on the back of the head looks ugly, painful and bizarre. Actually, there are lots of smaller jacks all over Neo’s trunk and limbs, which connect to the pod of the power plant. – “Conceptually, it’s a fluid-filled encasement with all sorts of organic and mechanical attachments keeping Neo alive.”4 Such a design is not only a necessary equipment, it can also be seen as “marks of a slave”– the proof of someone use to under the slave of the machine.

When we compare these designs, we could easily saw different design philosophies serve a similar function (connect people into the network.) As a design created by Japanese filmmakers, the jack-in interface in Ghost in the Shell clearly based on Japanese culture: convenience, compact, smooth, and elegant. Like a pair of headphones we wearing every day. On the other hand, as a design from American culture, the metallic hole on the back of character’s head shows complicate, cold, rough, and hideous – like a professional, powerful hammer drill. It might cause you injured if you don’t be careful.

Beyond the functional level, the different designs added different meanings to each film: for Ghost in the Shell, it helps to build a believable, advanced, hi-tech world – a world that almost everyone can easily connect to the network and accesses information, experiences, or even emotions. It is so convenient and easy, just like snapping a toothpick. But in The Matrix, the jack-in technology is developed by the machine, not by the human. This makes it very complicated and hard to use for normal people. It also reminds viewers the horrible truth that human being is enslaved by machine. The hole on the back of the head is like a symbol of humiliation. It emphasis the plot and helps the audience to understand the world in this film better.

Besides the different meanings, what more interesting is: both of the two designs are affected by ideologies. In Japan, most people believe modern technologies will make human’s life easier and better. There are lots of mangas and film works base on this belief. Such as Astro Boy, Doraemon series, etc. In comparison, there are always doubt and vigilance about technology advance in western world like Europe and America. Also, there are many literary and film works emerged, about technologies bring problems and become threatening to the human race. Like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Blade Runner, Avatar, only to name a few. Whether intentional or unintentional, the difference of ideologies is constantly reflected in the visual design of sci-fi movie.

Conclusion:

Firstly, by analysis the two representative examples above, we could see clearly that although there are many similar designs and scenes in Ghost in the Shell and The matrix, they served different purposes, and generated different meanings for the movie they belong. They might look alike but actually, play their own role.

Furthermore, according to the observation, there is also one thing in common between them: both of the two examples fit the image’s coding/decoding theory of Roland Barthes: denotation, connotation, and mythology. What we saw on the screen is the “surface” of a coded message (the denotation.) After an image has been read and decoded, we got the message under the surface (the connotation.) But how we thinking and interpret these meanings, whether consciously or unconsciously, is the mythology of images – the way filmmakers coding and hiding messages under the context of images, deliver them to the audience. As Roland Barthes puts it: “By endowing it with functions, which are, for the Photographer, so many alibis. These functions are: to inform, to represent, to surprise, to cause to signify, to provoke desire.”5

All in all, there is no “happy coincidence” in filmmaking. All visual elements we saw are intentional and well designed, to affect your feeling, to manipulate your mind, and eventually, telling a good story, create a great film.

References:

- Rose, Steve. “Hollywood is haunted by Ghost in the Shell”. London: The Guardian, 26 July 2013.

- Choo, Kukhee. “Visual evolution across the Pacific: the influence of anime and video games on US film media”. Commerce: Post Script, Inc. 28.2, Winter-Spring 2009. P.28.

- Clover, Joshua. The Matrix. London: British Film Institute, 2004. P.12.

- Wachowski, Lana. “The art of The Matrix”. New York: Newmarket Press, 2000. P.252.

- Barths, Roland. “Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography”. New York: Macmillan, 1981. P.28.

Leave a comment